|

The

enormous success of the Jazz singer in early 1928 had sent  Hollywood in a furore over the prospect of

talking pictures. Studios and theatre owners were divided in their

reaction to sound, but the voice of the public was clear

talkies meant big business. While many

producers debated the merits of converting to all-sound production,

Disney saw his opportunity to provide something unique: a synchronous

sound cartoon. Hollywood in a furore over the prospect of

talking pictures. Studios and theatre owners were divided in their

reaction to sound, but the voice of the public was clear

talkies meant big business. While many

producers debated the merits of converting to all-sound production,

Disney saw his opportunity to provide something unique: a synchronous

sound cartoon.

A

test was made if a scene for the third Mickey Mouse cartoon Steamboat

Willie. "When the picture was half finished, we had a showing

with sound" Disney later recalled. ”A couple of boys

could read music and one of them [Wilfred Jackson] could play

a mouth organ. We put them in a room where they could not see

the screen and arranged to pipe their sound into the room where

our wives and friends were going to see the picture. The boys

worked from music and sound effects score. After several false

starts, sound and action got off with the gun. The mouth organist

played the tune, the rest of us in the sound department blamed

tin pans and blew slide whistles in the beat. The

synchronism was pretty close. A

test was made if a scene for the third Mickey Mouse cartoon Steamboat

Willie. "When the picture was half finished, we had a showing

with sound" Disney later recalled. ”A couple of boys

could read music and one of them [Wilfred Jackson] could play

a mouth organ. We put them in a room where they could not see

the screen and arranged to pipe their sound into the room where

our wives and friends were going to see the picture. The boys

worked from music and sound effects score. After several false

starts, sound and action got off with the gun. The mouth organist

played the tune, the rest of us in the sound department blamed

tin pans and blew slide whistles in the beat. The

synchronism was pretty close.

"The

effect on our little audience was nothing less an electric. They

responded almost instinctively to this union of sound and motion.

I thought they were kidding me. So they put me in the audience

and ran the action again. It was terrible, but it was wonderful!

And it was something new!"

Exact

details of this now-historic screening vary from account to the

other, but the effect was the same on every participant. Ub Iwerks

later said, "I've never been so thrilled in my life. Nothing

since has ever equalled it" The tiny Disney crew which

consisted of Walt, Roy, Ub, Les Clark, Johnny Cannon and amateur

musician Wilfred Jackson had discovered the miracle of talking pictures.

Audience

reaction to the completed Steamboat Willy duplicated the excitement

of that private test screening months earlier. The idea that make-believe

cartoon characters could talk, play instruments, and move to a

musical beat was considered nothing short of magical.

In 1932 the distinguished critic Gilbert Seldes noted: "The

great satisfaction in the first animated cartoons was that they

used sound properly the

sound was as unreal as the action; the eye and the ear were not

at war with each other, one observing a fantasy, the other a actuality.."

Edited excerpt p. 34 - 35 Edited excerpt p. 34 - 35

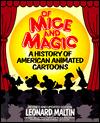

Of

Mice and Magic : A History of American Animated Cartoons

by Leonard Maltin

Paperback

- 485 pages Rev Rei edition (May 1990)

|